This year has had its challenges! My parents have had a tremendous number of health issues, which has occupied a great deal of my attention. Amazon destroyed its Kindle Periodicals program, through which the majority of my magazine’s subscribers got their copies. The implosion of Twitter meant it became much harder to connect with readers and potential Patreon supporters. And AI has consistently threatened writers and artists across the spectrum, raising tension throughout the creative world.

But it’s also been a fantastic year on many fronts! My first-ever screenplay won first place at the HP Lovecraft Film Festival. I was nominated for a Locus award for Best Editor, and stories in Nightmare were nominated for the Locus, Shirley Jackson, and Nebula awards. I also had a short story nominated for a Shirley Jackson award — my first fiction award nomination. I had a few short stories come out, and my recent SF short “An Infestation of Blue,” had made it to the Nebula Recommended Reading List. I sold a couple of short stories, and I finished the first draft of a novel. I enjoyed working with several great coaching clients, and I didn’t miss a single post for my Patreon supporters. I went on a tremendous road trip with my family (more than 2800 miles!), brought my mom to live with me, and ran a tough trail half marathon where I didn’t even finish in last place. 2023 might not have been my most productive year, but I kept on soldiering along.

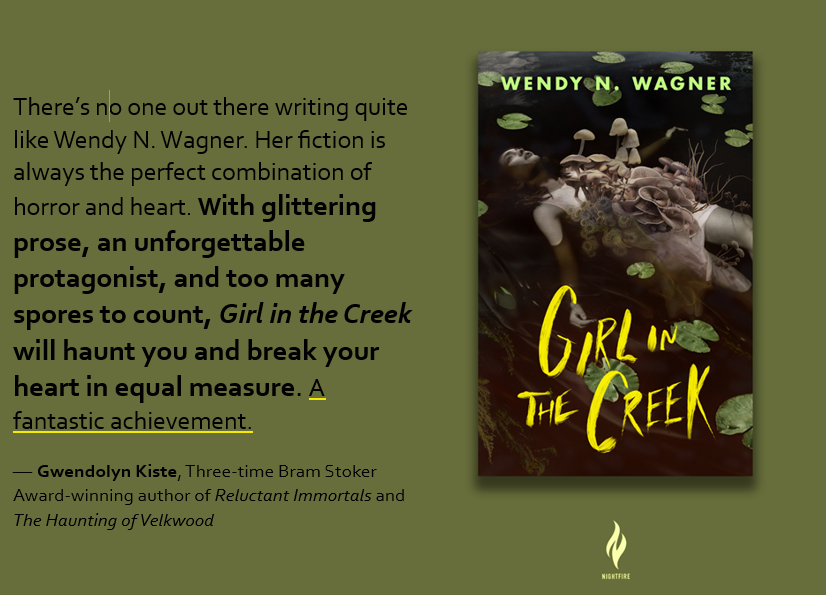

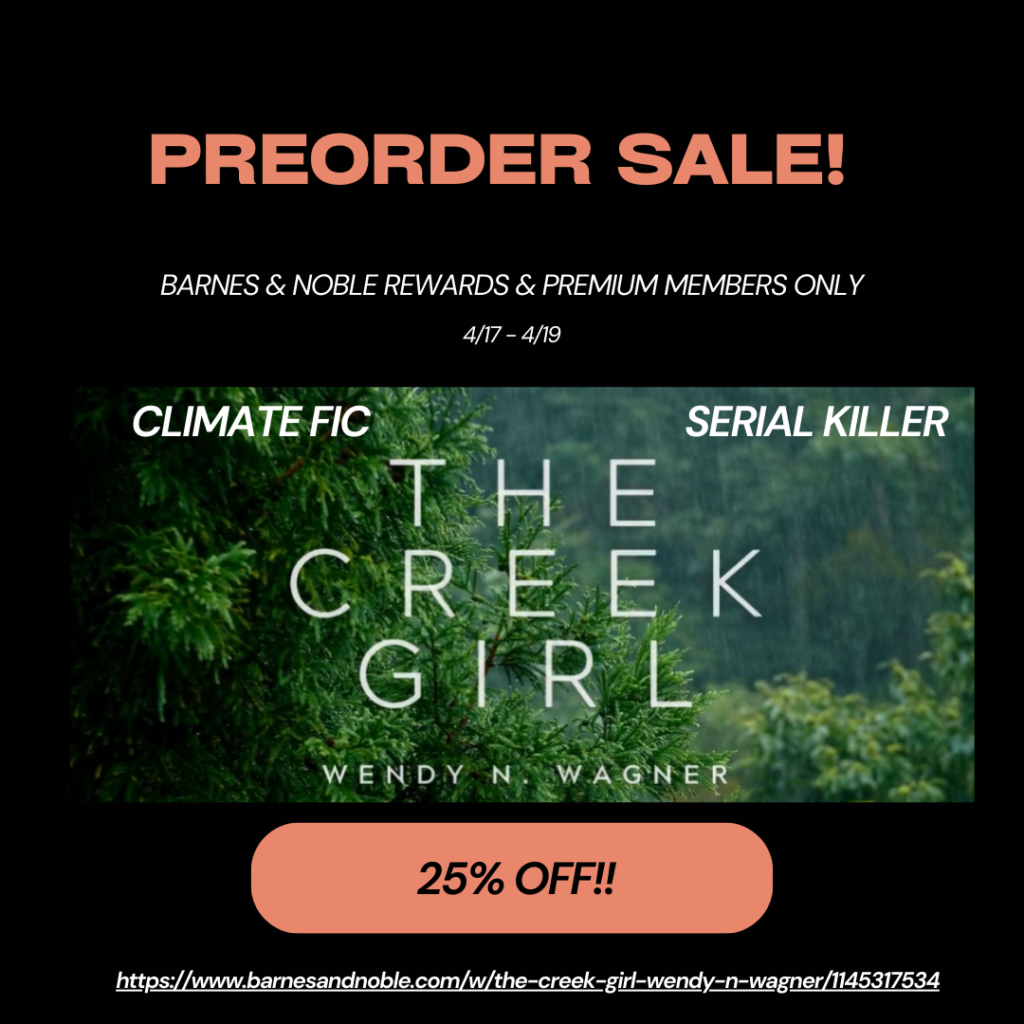

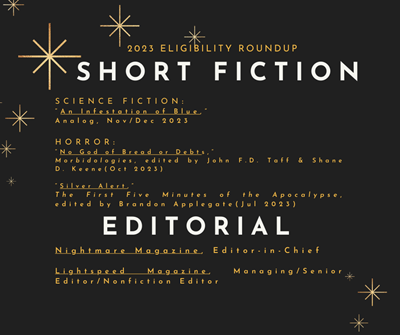

Like many others, I’ve turned to Canva to make a cute shareable eligibility image, which is shown below. For more details about the work, check my bibliography page. I have three stories that are eligible for the Nebulas and Hugos, and two horror stories to consider for the Bram Stokers. I’m also extremely proud of my editorial work again this year — both Nightmare and Lightspeed have released terrific work!

I hope you all have had good experiences in 2023 and that you join me in looking to 2024 for good news, great time outdoors, and all the creative energy we could ask for. Let’s make it a terrific year!